Probably the first real decision I had to make on my whirlwind experience as PSM of Ogunquit’s “Mary Poppins” remount at the Music Hall in Portsmouth, NH, was to take a site visit of the venue and choose a calling position.

I’ve probably talked about my thought process before. When I was on the road my general pattern was that if a venue had proper video and audio monitors or sightlines to the stage, I would call from the deck. Partially this was because we were in a new theatre nearly every day, and I was very comfortable with the show and wanted to mix it up. Also, walking back and forth to the booth is annoying and sometimes lonely. And not just lonely, but I think bad for morale because I can’t be a part of the backstage life as much.

However, I also liked to call from a nice booth, because it’s easier to really see what’s going on in the show, and judge its whole impact on the audience from their perspective. If you know a show well you can call cues from backstage and know they’re doing what you want, but when in an unfamiliar situation (either a new show, or a venue with significant differences), it’s the only way to know you’re really calling things right.

So I was torn. I wasn’t going to get much time at the tech table. I was really unfamiliar with the operation of the deck, having left that to my ASM Daniel, who already knew the show, while I spent the 6-day rehearsal process focused on learning the show itself and the placement of my cues in it. Being backstage seemed like it might give me a better understanding of how the show operated, and a perspective on what was going on during a problem. Also, I’d be able to spend more time checking in with the actors and crew and generally making sure everything was running smoothly. And I might actually get to know the ensemble, who I hardly ever saw in rehearsal.

We got the site tour, and I was shown my two options, and took photos so that I could look back at them again if I needed to re-consider.

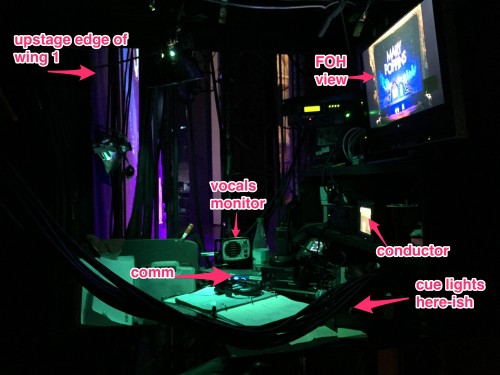

The first option was backstage under a little dimmer platform, behind a short downstage arbor, looking through the ropes. It was a weird view, but not awful. And the legs and ladder for the platform overhead provided a nice barrier to give me some personal space (the ensemble dubbed it the “jungle gym” when they saw it). The sightlines upstage reached to the upper edge of wing 2 across the stage, and only wing 1 on my side, of course. Not perfect, but pretty good for where our scenes played, and there was a decent amount of room to lean in either direction to see upstage or down to the apron. Due to the intricacy of the “Bert walk” Foy effect, in which an actor walks and dances up the proscenium, over the top upside down, and then down the other side, my first caveat was that I would only call from backstage if I had a camera view sufficient to clearly see the position of his feet all the way across. I was told I could.

The other option was a booth in the balcony, which was not luxurious but not tiny either. The view was almost-center and unobstructed. There was an optional window (which I said I would want to keep, and add an audio monitor). I’d have a nice view of the gorgeous theatre, and a far away and steep, but clear view of the stage. My “cons” about the booth were the fact it would be a real hike to get to, and it was a little far away for the kind of acting-based cues I already knew I would have, and wanted to be able to do justice to. I felt confident I could see those kinds of moments better by watching them sideways from backstage.

There was a third option, of an open desk adjacent to the booth in the balcony, which was where the light board ended up. That was vigorously and immediately ruled out by me, and by Daniel on my behalf, that there’s no way to call such a show from the audience.

Finally the tour concluded back on the deck, and the venue’s TD turned to me with the words I was dreading, “So where do you want to call from?” I hemmed and hawed. Daniel had told me that my predecessor had called from stage right in a similar position, without any particular problems, so that assured me it was a basically sound idea. I had him come look again at the backstage desk with me, and try to imagine what issues I wasn’t thinking of. There would be guys flying at the arbor in front of me occasionally, but that’s why I have a camera. So I went with stage right.

The end result

When we arrived for the day of our dry tech (yes, we did a dry tech, which in my experience is rare and usually not that helpful, but definitely allowed us to save six hours of headaches without the actors on the clock), the calling position was still buried in other equipment, so I remained in denial for a while and got comfy at the nicely-apointed tech table I was given.

I familiarized myself with the cue light system our ME had provided. This was a fun process because the only limitation I was given was that there were eight switches, and I could ask for whatever Daniel and I wanted them to do. We met up on a lunch break (because we were pretty much rehearsing in separate buildings the entire time), and hashed out our needs and desires.

What I requested was:

- On the deck, ropelight running the depth of the stage on both sides — red, blue, and green, the colors on both sides controlled by a single switch. High enough to be visible from across the stage, so you can see your light no matter which way you’re facing. I requested red/blue/green, but they were plugged in as red/green/blue, and by that point I was actually considering doing that anyway, so we kept it, as red was primarily rail, green was primarily traveler moves, and blue was primarily (and by the time we opened, exclusively) set moves, so it made sense to keep red and green together.

- A yellow cue light on the fly rail (both sides — it’s a hemp house). A second color here was on our wish list, but we sacrificed it to split the downstage lights into left and right. We planned to call this light Tinkerbell, if indeed we were able to get yellow (as we had our meeting the day after an epic Peter Pan Live-watching party), but to be honest by the time things calmed down enough and we got friendly enough with the crew, I had totally forgotten about it, and am just remembering it now. Which is a shame. I think they might have liked it.

- Independently-controlled downstage cue lights in wing 1 on either side (colored blue for minimum distracting spill if they glowed in view of the audience).

- Sound

- Conductor

I went home that night and stayed up till some ungodly hour matching the switch numbers to the cues in my inherited script, and re-ordering them in the script to match the numerical order of my chosen layout. Daniel provided me with his work-in-progress run sheets, and a list of where each flying piece was operated from (some from the fly rail, some on the deck), and as I went through the show I checked for any transitions that couldn’t be accomplished with our design. There were a few re-warns, but easy enough to do.

I sent our request to the ME, and heard back soon that it should be attainable. When we arrived to dry tech, I met him for the first time, and immediately got some evidence of his sense of humor. The conductor’s cue light was a Christmas tree. Not Christmas tree lights. Not lights in the shape of a Christmas tree. Not even a tiny light-up plastic Christmas tree. I mean an actual (fake) stand-up, leaves-and-all Christmas tree, maybe 2 feet tall, strung with multicolored lights, and sitting smack in the middle of the pit. It’s one of the most whimsical things I’ve ever seen in a theatrical operating environment. The pit was not sunk very low below the audience, so it wouldn’t have been subtle in the event I needed to contact him during the show, but I only needed to do that once, and I was stopping the show during the overture because the house lights weren’t responding.

Backstage the Jolly Holiday cheer continued (yes, we know “Jolly Holiday” doesn’t mean holiday like we say in the States, and this was a matter of great debate in a marketing sense, but the pro-Jolly-Holiday contingent won out over the sticklers for accuracy, and we frequently threw the word “Jolly” in whenever it was mentioned that this was a holiday-season-based production).

Instead of finding red, green, and blue rope light, we found green and blue Christmas lights, and candy-cane-striped rope light. I decided to go for the morale boost of changing whatever calling muscle-memory I had developed in the rehearsal room, and to warn on the “candy cane” rather than on the Red. It was only two more syllables, though the hardest thing about learning to call the show was to fit the warnings in. I think the candy cane is what distracted us from calling the yellow cue light Tinkerbell (or “Tink” as I suggested it would have to be called, for the aforementioned syllable-rationing reasons). I think by the end of the 8-show run I was comfortable enough that I could have called it “Supercalifragilisticexpialicuelight” and could have made it work.

All the other lights were conventional theatrical cue lights, but the Christmas-y feel when our three main deck lights were lit seemed to put everyone in the holiday spirit. When we discovered an actor had a hard time hearing a dialogue cue to enter through a door, I suggested a cue light, and chose the candy cane simply to be festive.

I was very grateful that the switches were up-and-down and not left-to-right. I kept saying to Daniel, as I practiced with mock cue lights in the rehearsal room, “If these switches are sideways I’m gonna cry!” The really heavy toggles are not my first preference, but the orientation, spacing and reliability were so good that it was still better than most possibilities. I have short fingers, and the panel was angled relative to my body, so I had trouble reliably getting an equal distribution of force to get all the lights off exactly together when throwing 4 or 5 switches at a time. There were quite a few 4-at-once cues, but only one 5-at-once, and most of the time it was a little scary, as my fingers would sometimes slip off the sides without throwing the switch, but it all worked out.

The calling desk

When we finished tech (a day for each act, ending a little early each day, which disappointed me a little, but was respectable), we only had one afternoon for a dress before our first preview that night. So the night before I was faced with my second-most-nervewracking question: did I want to call the sole run from the tech table or the calling position? And I chose, as I always do, the calling position, as if there’s something totally unworkable about it (can’t see or can’t hear), I’d like to discover that in a rehearsal I can stop, and not with an audience in the house. It was especially a no-brainer on a show like this, where there are only a few dropping-flying-things-on-actors dangers, but a number of Foy cues, the clear operation and calling of which was of course given priority over anything else on the show.

But the downside was that I never got to call the show from the house, so I was flying a bit blind as far as the artistry of calling the show. Tech wasn’t all that helpful from an artful-calling perspective because we didn’t repeat sequences very often, and I was so focused on getting the set onstage and getting all the words out, that I didn’t usually have any time to call a light cue and study it in depth. And a lot changes as the designers tinker anyway.

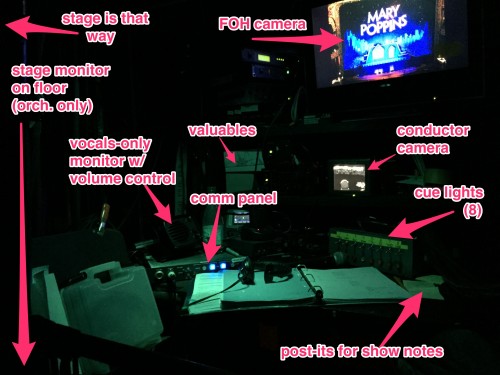

So on the day of our first preview, having never called the show (which was an awful feeling!) I approached the calling desk with trepidation, to figure out how I would set it up. If I faced the stage, the monitor with the front-of-house view would have been just behind my right shoulder, and I’d have to call on a steeply-pitched music stand, which is not my cup of tea. I didn’t like that prospect. If I faced the monitor, my script could be on the desk, but I’d have to turn a full 90 degrees to glance at the stage.

Quite sensibly, I decided to try splitting the difference. If I called the show diagonally, I wouldn’t be facing anything of use, but I’d have the comm and the volume adjustment for vocals over my script, and closer to my left hand, and the cue lights in front of my right hand. The stage would be a 45 degree glance left, and the monitors a 45-degree glance right. And my chair swiveled, so I could pivot as the moment required, to watch the stage more comfortably, or to use both hands (as I usually had to) to throw cue lights. It felt pretty comfortable as I set things up and imagined myself calling the show.

The front-of-house camera ended up being an interesting situation. Originally it was in the booth at the center of the balcony. It was a great view, until the curtain call of the first preview, when we discovered that when the back row stood up (a good problem to have — the back row was always full, and they always stood), they completely blocked the camera. I called the spot pickup for Mary’s bow based on where she was approaching behind the ensemble when I last saw her. I have no idea if it was right. And then I was like, “Well thank God the rest of the show is all musical cues!” and I proceeded to call the 3-minute finale totally blind from FOH.

When we discussed it at the production meeting that night, I was asked if I would be OK with it being somewhat off-center, as that was the only location available to mount it high enough. I didn’t think I’d ever used a significantly off-center camera, but the show didn’t have a single “when _____ gets to center” cue (except for stopping Bert at the top of the proscenium during the Bert walk, which is a musical thing, and his feet are literally right below the ornamental decoration at the middle of the proscenium, so it’s easy to tell). I didn’t feel it would be a problem even if it was somewhat noticeable. But the distance between camera and stage was so great, I really couldn’t tell. The photos here were taken after the move was made. I basically forgot all about it.

The conductor camera was a tiny one mounted above his music stand, and had a perfect view, and as an added bonus, clearly showed a good chunk of the audience, which was helpful for observing audience reactions (if they’re quiet, are they at least smiling?) and the timing of the standing ovation.

I didn’t use the music stand in front of me (which was bolted to the desk) for much. I put the God mic on it (sometimes with a post-it to remind me of things I wanted to announce), and whatever else I needed to store.

Over the course of the short run, I really fell in love with the layout. It wasn’t perfect, but I think I really got the most ergonomic solution out of the situation I was dealt. The audio deal was actually cool, too. At my feet was the stage right monitor for the actors to hear the orchestra, which of course had no vocals, but as much music as a body could want. Our sound designer then gave me a small monitor right in my face with just vocals, that could be adjusted from soft to deafening with a quick flick of my hand up from the talk button. It was actually better than most situations because I couldn’t control the volume of the band, but I could make whatever mix I wanted of vocals vs. music.

Being backstage was a great advantage. It accelerated my understanding of how the scenery shifted around in the very crowded wings during the show, which was incredibly helpful in managing issues as they came up. The one thing I was a little disappointed with was that the pace of the show and the packed backstage space allowed for very little direct contact with the cast during the show, which is part of the reason I like calling from backstage in the first place.

But I was really happy with how this arrangement worked out, and I hope it gives you some ideas for brainstorming the next time you’ve got a challenging calling desk setup.