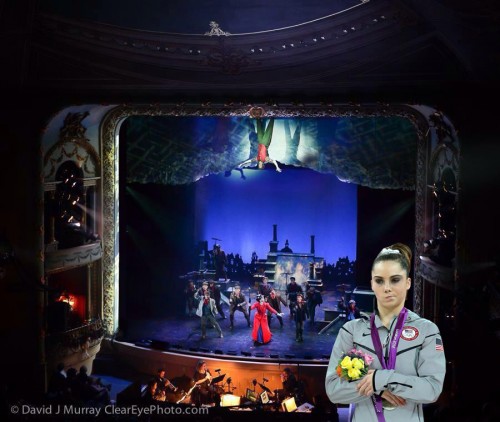

This is sort of an addendum to my recent post on how I chose my calling position on Mary Poppins. I was going to go into detail about the advantages I experienced calling from backstage, and eventually realized I had so much to say about it that it could really be its own post.

This is sort of an addendum to my recent post on how I chose my calling position on Mary Poppins. I was going to go into detail about the advantages I experienced calling from backstage, and eventually realized I had so much to say about it that it could really be its own post.

The most basic and practical advantage to calling from backstage is that you don’t have to walk far to get there. First of all, the stairs to the balcony were particularly exhausting in this venue, and the whole path went through the audience, so the travel time could be seriously delayed to get through the crowd. I’ve definitely started shows late because of a crowded front-of-house. Once situated in a booth, there are plenty of things that I might want or need from backstage that I would forego because it would take too long, or too much effort, to go back. And you don’t have to compete with the line at the ladies’ room if you can go backstage. I mean you still have to compete, but there are less potential pee-ers, and they will generally let you go ahead if they see you waiting.

But the most important thing to me about calling from backstage is that I think it’s better for morale because I get to spend quality time with the cast and crew as we work together to make a performance. Often when in a run I feel like I don’t see the cast enough. If they keep to their dressing rooms before the show, and I’m in the booth the entire show (maybe not even coming down at intermission if it would take too long to fight the crowds), then we never really see each other and it can feel a little distant. I always expect the ASM to get closer to the cast than I am, but I also don’t want to be a shadowy figure sitting behind glass who is only accessible by passing messages through someone else. Especially when I have such a fondness for a cast as I did on this show, I wanted to have easy access to them, and for them to feel like I was around if they needed to talk.

The Check-In

I made it a point — before every act, and at the end of the day or show — to set aside at least two minutes to make a pass through the 2nd-floor crossover where all the principals and most of the Equity chorus had their rooms. I usually made it to the ensemble rooms in a dead-end tunnel of the sub-basement, about once a day. I didn’t bother people if their doors were closed (unless I specifically needed to talk to them), but I made sure everyone knew I was passing through if they had anything to say, and our Mary and Bert generally got some kind of direct contact of at least a quick “Everything good?”, “How did your flight feel?” etc.

Sometimes it was nice just to say hi, and participate in the social life of backstage. There was one room in particular that I often stopped in not because I expected the occupants needed anything, but because I knew they’d probably have something interesting to chat about.

During one performance I was having a really frustrating first act dealing with technical issues, and found a gaggle of actors and musicians gathered in the hall, and joined in on their conversation with an “is everybody having a better show than I am?” This was a good opportunity to explain what the hell was going on and that it was fixed, and have a laugh about what the actors were thinking onstage, and totally unexpectedly I got a very good backrub through most of the conversation. I absolutely delayed places because I was getting a backrub and being entertained out of my frustration, so I was glad when I finally got to the calling desk to hear the house was requesting a 20-minute intermission. Seriously, knowing when your stage manager needs a backrub is a special skill, and if you’re calling from the deck there are dozens of people nearby, one of whom might possess that skill. It probably isn’t your light board op.

There was one show in particular that I thought was a fantastic performance but the audience was kind of lackluster, so I went upstairs when we came down, just to make sure I wasn’t imagining things, and the cast felt as good about it as I did. They were glad to hear that I agreed it was their best show, even if the faces out there in the dark weren’t giving them a lot of support.

I find that my mood can sometimes color my impression of a performance, so I like to have some kind of verification before I say something in the report like “This was the best show ever, and the other 900 people who saw it are wrong.” Being backstage removes a step from that process. A lot of the time I find myself asking the ASM, after everyone has gone, “how did the cast feel about tonight’s show?” and well, that’s kind of a lame way to do it. Also, I went up there selfishly looking for material for my report, but when I got there I saw the real benefit in the faces of the actors, who were genuinely thankful to hear that somebody noticed what a good show it was, and you don’t get that by doing it through a third party.

But when I wasn’t getting backrubs and giving pep-talks, I was doing the real work of keeping the show running: getting things done and fixing the show. Rather than avoid opening the door too wide to any and all complaints and requests, I welcomed it. My attitude was to put myself in everybody’s face as often as possible, in the hopes that they would tell me how I could make their show better.

I should note that this is not my usual M.O. It’s something I think I could work on, so I used this opportunity, and this lovely group of actors, to play with cranking my accessibility up to 11, to see just how helpful I could be. Part of what made this possible was how well-supported I was by management and crew. I had all the time in the world to take care of the cast because everybody else was doing their jobs. And the cool thing is, when you’re not stuck doing things that aren’t your job, and everyone else is able to do their jobs well and without much supervision, the PSM actually doesn’t have a lot to do, except be around to find out what else can be done better.

This was the case even sometimes in the middle of tech. I love when we can take a 10 and I literally have nothing to do for 10 minutes. And because I’m sometimes a bit calculating with how my behavior affects everyone else, rather than just sit at the tech table tweeting for 10 minutes, I often took advantage of the opportunity to show my face around the theatre — in the dressing rooms, on the deck, in the lobby where the producery-types had made their office — specifically for the purpose of being like, “Hey. No, just saying hi. How’s it going for you? Oh, there’s a funny YouTube video of Mary Poppins as a horror movie? Let’s all stand in the middle of the stage and watch it right now, cause your tech is going so well that this is what your PSM is doing.” I know from previous feedback that this kind of thing works wonders in everyone else having an enjoyable tech, so in addition to watching YouTube videos, I began my dressing-room-hallway flybys, just to show that although tech isn’t about the actors, this tech is so under control that it could be about the actors if they needed anything. With this pattern established, I made it a predictable occurrence as we continued into the run, in the hopes that people would think of things to ask me, secure in the knowledge that any problem they had could be taken care of swiftly.

It became something of a game for me, which is actually a very Mary Poppins life lesson, about making things that could be work seem like fun. I challenged myself to make sure that any note I was given was fixed immediately, whatever bad thing was happening never happened again, and any question, if I did not know the answer, I quickly hunted down the right person and came back with an answer. Anything from issues with the heat, to props getting stuck on scenery, to missed mic pickups of lines that aren’t in the script, to broken dressing room chairs, to soap running out in the mens’ room, to escorting backstage guests was something I enjoyed providing prompt and effective service on.

My proudest moment was a team effort, as one night after the show our PA alerted me to a potential problem that I hadn’t heard about. I was flabbergasted — it seemed impossible that this could be a real problem (a safety issue, no less) that had gone unreported with the amount of time I spent hanging around, prodding everyone to think of anything that was on their mind. I suspected one of those situations where something happens in the heat of the performance, and by the time there’s an opportunity to tell someone, it’s three scenes later and long forgotten. And then the next night it happens again, and the cycle continues.

So next intermission I swing around the dressing room door with, “Hey, I don’t know if this is a thing, but is there a scene change in Act II where you could potentially get crushed?”

“Yes! I almost die every night! How did you know?”

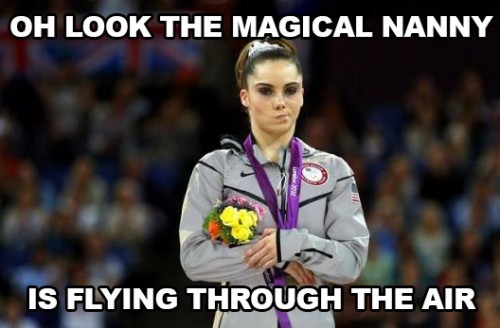

Because I am your magical PSM. If you don’t remember to tell me when I make my check-ins (many of which you actually answer with a cheery “I don’t feel like I’m going to die”), my magical minions have eyes everywhere. And now that I know what’s happening from your perspective, we can employ a change right now, ensuring you will never be nearly-squished again. #dropstheheadset No but seriously, I gave our PA most of the credit, cause it takes a village to keep a cast alive.

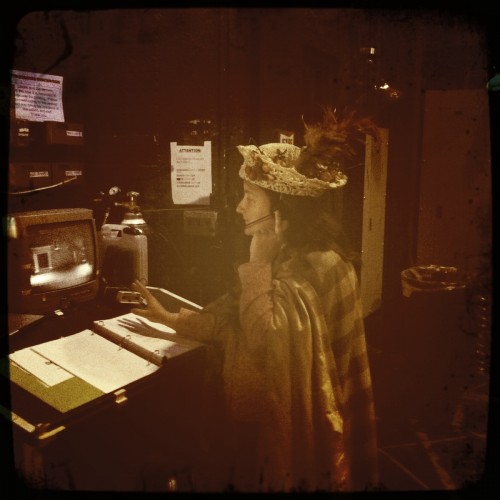

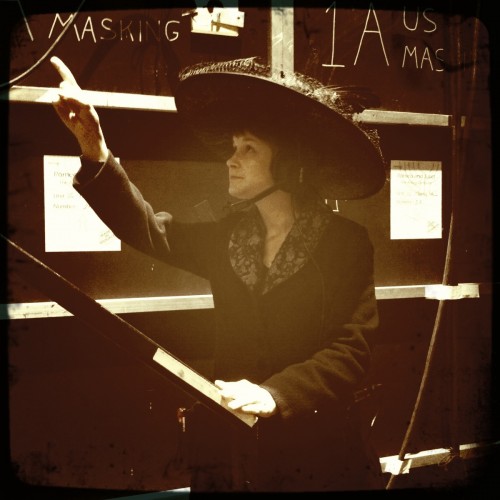

On the Deck

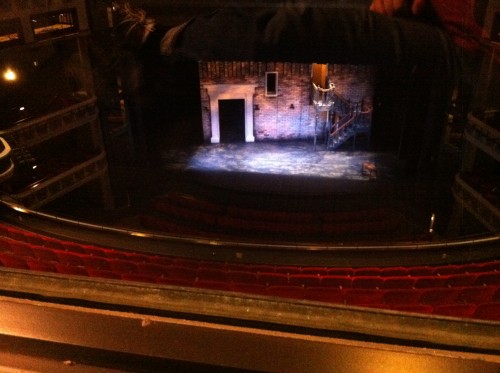

As I said in my earlier post, I was disappointed how little contact I got with people while the show was going on. The deck was crowded, and as a result everyone instinctively knew that if you were hanging out, you were going to be in the way of actors, crew or scenery who had a need to be where you were standing. So there wasn’t a lot of hanging out, at least not downstage right, and due to large chimneys and houses stage left, I’d imagine people got the hell out of there, too. Or maybe waited on top of chimneys and houses for a while, I don’t know.

When I picture calling from the deck, I think of those moments where you know you’ll see certain people. Maybe you have a little ritual you develop for that moment. And it’s important to learn the times during the show that you have a chance to get a word with people of note, if the need arises — your ASM, your head carp, your leads (especially those who rarely leave the stage), the dance captain. We did eight shows in five days, and I know if we’d run longer things would have relaxed enough to allow for more of that, but the inherent pace and structure of the show still would have limited it.

As it turned out, the moments I had any chance to talk to people were almost nil. The stage right offstage singing position was right behind me, which you’d think, “cool!” Yeah, but I’m still calling cues, and they’re singing, so every time I had the impulse to turn around and wave, I realized I’d be calling a cue right into somebody’s mic. And the moment they were done singing, they were scampering down the stairs to their dressing room to get out of the way and make their next change. So much for that.

The number of times in the show where an actor was standing next to me in a moment of calm for the both of us, for long enough to speak words? One. ONE. It was at the top of “Feed the Birds,” when Mary and the kids arrived for their entrance. The whole time they were there was maybe 20 seconds. In reality, between me finishing calling the scene change, and them moving into position to enter, it was more like 5 or 10 useful seconds of communication. Make eye contact of the “everything good?”/”good” variety, and then maybe a couple extra seconds for pleasantries, like actually saying those words out loud, or perhaps a brief comment on the performance, and off they went. A couple times there was something of actual content to say, like we’re working on the monitor issue. But the good thing was that we had eight deck crew members on headset, plus the A2, so in the event anything important had to be said between me and any actor, they could always find a nearby crew member to tell, and whenever I asked, “Is anybody near so-and-so?” the answer was always yes. So the in-person check-in was really just for socializing, or sharing anything not urgent enough to interrupt anyone, but I was still sad that I barely saw anyone.

Occasionally crew members or ensemble on their way downstairs would spend a moment standing behind me watching the show on the monitor, but the pathway would not be able to be blocked for long. My friend Jimmy, who played Robertson Ay, had a significant amount of time offstage, and would sometimes tuck into my jungle-gym (if you haven’t read the other post, I was under a platform, and the ladder and legs of said platform provided me with a footprint of personal space), to watch for a while. One night we had a prop get stuck on the apron and needed to get it struck, and of course the one time I needed to send him onstage as actor-conveniently-dressed-as-a-butler, he wasn’t there with me (and, I should correct myself, this was the one time when I asked “is anybody near so-and-so?” and nobody was, because his dressing room was in the bowels of the earth).

Word to the wise: make time to find out in advance how audible your paging system is to the audience if used during a performance. I would have paged him to come to the calling desk but I didn’t because I was afraid it might be too loud onstage. So instead we sent out a stagehand-conveniently-dressed-as-a-stagehand during a scene change, which is not quite as slick. Although if you’ve read my other Mary Poppins post, Being Too Clever, you would know that our attempt to solve the problem elegantly would have inevitably resulted in something far worse than an audience seeing a glimpse of a burly black-clad figure in the dark.

After the first few days of controlled chaos, things did calm down enough that the crew was able to wander over to chat once in a while. Our crew chief spent most of his track flying at the arbor right in front of me, so we were usually within sight of each other. Daniel, the ASM, was also able to be around more and more as things settled down. There were a few times when the three of us being able to chat off-headset while the show was going on helped us to better plan our response to unexpected situations.

Other than the fact that the show itself made things so crowded and crazy, calling from backstage was everything I hoped it would be and more. As I had hoped, I had good line of sight to the actors during most of the scenes. Although I never noticed how many of the Mary-snaps-and-something-happens cues were staged with her in my blind spot midstage-right. The ones where I could see her were a lot of fun. The ones where I was going just on knowing her timing and an incredibly blurry and low-contrast figure on a monitor were terrifying. I think I usually got them, but who knows. I have vague memories of getting completely psyched-out once, but I took my rehearsal-hall mock calls very seriously, so it’s possible that feeling of abject humiliation happened not only not in front of an audience, but quite possibly not in front of anyone. Which didn’t make it less terrifying.

The show had an unusually high number of cues that could be taken on acting beats, and that number grew higher the more I saw of the acting. With such performances to hang a cue on, who needs words or blocking to mark the separation between one thing and the next? It was a great advantage to be so close to the stage for all those cues. They were the easiest to call. I guess it also didn’t hurt that in the typical bane of my stock existence, I spent every single rehearsal with the principals. So I could write a paragraph to describe the moment in Christiane’s acting upon which a light shift from the living room to the office will occur, but I couldn’t call the dance break of “Step in Time” without counting it. But honestly, what I found — contrary to my expectations — was that the show is more about that shift from the living room to the office than it is about dancing chimney sweeps. Except Bert dancing on the ceiling. I literally considered my job description to be (1) be able to call the Bert walk correctly, by heart, every time, before we ever set foot in the theatre. (2) Call the rest of the show. (3) Schedules n’ shit.